Exactly how I felt when I first encounter deferred tax. #truestory

The reason is because it is quite difficult to grasp the concept of deferred tax. For me, when I was a student, I know the rough idea on how to calculate deferred tax but I always couldn't grasp the concept and meaning of tax base. I tried to read the definition of tax base in the standards (refer below):

The tax base of an asset or liability is the amount attributed to that asset or liability for tax purposes.

|

| Apa maksud oui? (Translate to what do you mean?) |

Let's dig further for more definition from IAS 12.

The tax base of an asset is the amount that will be deductible for tax purposes against any taxable economic benefits that will flow to an entity when it recovers the carrying amount of the asset. If those economic benefits will not be taxable, the tax base of the asset is equal to its carrying amount.

The tax base of a liability is its carrying amount, less any amount that will be deductible for tax purposes in respect of that liability in future periods. In the case of revenue which is received in advance, the tax base of the resulting liability is its carrying amount, less any amount of the revenue that will not be taxable in future periods.

Normally by this point, my mind will shut down. Don't worry, you are not alone if your mind shut down at this point.

As such, I intend to write some blog posts (in a few parts) to share with you about the methods that I used in determining tax base. I will give you a few scenarios to consider together with the detailed explanations behind the logic of determining tax base.

This post is relevant to you if you are taking the Financial Reporting (FR) paper or Strategic Business Reporting (SBR) papers in ACCA.

But before we delve into the details of how to determine tax base, it is important that we understand the basic concept of deferred tax. This shall be our focus for Part 1.

Concept of Deferred Tax

The main idea of why we recognise deferred tax in the financial statement is basically due to the difference between accounting rules (i.e. IAS / IFRS) and tax rules (e.g. in Malaysia, we need to follow Income Tax Act 1967).

|

我们不一样 每个人都有不同的境遇 (Sorry, suddenly I feel like singing this song 😂) |

The difference between accounting rule and tax rule will result in the difference between accounting profit and taxable profit (in Income Tax Act 1967, taxable profit is known as chargeable income). Some examples of such differences are listed below:

- Some expenses are not deductible in arriving at taxable profit. For example, entertainment expenses to potential customer, penalty and fines, purchase of land are non-allowable expenses under Income Tax Act 1967.

- In accounting, we charge depreciation if we have property, plant and equipment (PPE). However, in Income Tax Act 1967, depreciation is non-allowable expenses. Instead, capital allowance (also known as tax depreciation) is given if the asset is a qualifying asset. Normally, depreciation expense and capital allowance will be different.

- Some expenses are accrued in the financial statements if it is incurred. However, for income tax purpose, it can only be deducted if the payment is made (i.e. deduction is on cash basis). For example, in Malaysia, secretarial fee and tax filing fee is deductible only if it is incurred and paid (refer to Income Tax (Deduction for Expenses in Relation to Secretarial Fee and Tax Filing Fee) Rules [P.U. (A) 336/2014] for more information).

- Some income are deferred in financial statements (e.g. when a company receives advance payment for service to be rendered in the future, the income is not recognised as revenue in the Profit or Loss. Instead, it is recognised as deferred income in liability), but according to the income tax rule, it might be taxed when the entity receive the income (e.g. according to Section 24(1A) of Income Tax Act 1967, advance payment in relation to services to be rendered in the future will be taxable when it is received).

To understand the difference better, let's consider the following scenario:

Scenario

Assuming that an entity has profit before tax of $100 from year 1 to year 5.

The entity has an asset which costs $100 and the expected useful life of this asset is 5 years. The depreciation is $20 per year ($100 / 5 years) and this depreciation is already included in the profit before tax of $100.

For income tax purpose, depreciation is non-deductible expense. However, this asset is a qualifying asset. In year 1, the entity can claim an initial allowance of 20% on cost as well as annual allowance of 20% on cost (i.e. a total of 40% in year 1). Subsequently, the entity can claim 20% annual allowance for year 2, 3 and 4 (i.e. until 100% of the cost is claimed).

The applicable income tax rate is 25%.

Let's look at the income tax calculation for this case:

As we can see above, there is a difference between profit before tax (accounting profit) and taxable profit for year 1 and year 5. Even though we pay income tax at 25%, the effective tax rate for year 1 and year 5 is not 25%. This is because:

1. In the first year, we get to claim a total of 40% capital allowance and this is higher than the depreciation of $20. As such, the tax expense in year 1 is lower.

2. In year 5, after we have claimed all the capital allowance in year 4, we will have a higher tax expense because there is no more capital allowance for us to claim in year 5.

Such variation in tax expense and effective tax rate can be very misleading to the users of financial statements as it doesn't give the true picture of the income tax expenses that the entity needs to pay.

|

| Le face of the users of financial statements, if we managed to successfully confuse them. |

Refer to the explanations below:

Year 1

In year 1, we will recognise additional tax expense of $5 as well as a deferred tax liability of $5. Refer to the double entry below:

Dr Tax expense $5

Cr Deferred tax liability $5

The reason for such entry is because we will be paying extra $5 income tax on top of $25 tax expense in year 5.

Years 2 to 4

No adjustment is made to the tax expense in year 2 to 4.

Year 5

In year 5, we will reduce the tax expense by $5 (reduce from $30 to $25) as well as reduce the deferred tax liability recognised in year 1 by $5 (reduce from $5 to $0). Refer to the double entry below:

Dr Deferred tax liability $5

Cr Tax expense $5

Conclusion of Scenario

As we can see, after the adjustment for deferred tax, the effective tax rate is now consistently at 25% from year 1 to year 5. This is a better presentation as it gives a better picture of the tax expense to the investor. As shown below:

|

| Now your financial statements look more handsome. Congratulations! 😂😂😂 |

Note: The above is just an illustration of how deferred tax works. You are not allowed to use the above method in the exam.

Methods to be Used in Exam

The correct method to calculate deferred tax is by comparing the carrying amount (CA) and the tax base (TB) of the asset.

CA means the net book value of the asset, whereas TB means the tax written down value of the asset (i.e. cost minus capital allowance). Refer to the following table for the comparison between the CA and TB of the asset for year 1 to year 5.

Methods to be Used in Exam

The correct method to calculate deferred tax is by comparing the carrying amount (CA) and the tax base (TB) of the asset.

CA means the net book value of the asset, whereas TB means the tax written down value of the asset (i.e. cost minus capital allowance). Refer to the following table for the comparison between the CA and TB of the asset for year 1 to year 5.

1. The CA of the asset is calculated by taking the cost of the asset ($100) minus the depreciation. For example, in year 1, the CA of $80 is equal to $100 minus depreciation of $20.

2. The TB of the asset is calculated by taking the cost of the asset ($100) minus the capital allowance. For example, in year 1, the TB of $60 is equal to $100 minus capital allowance of $40.

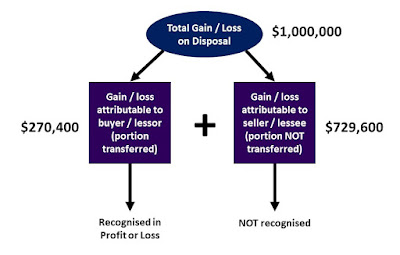

3. The difference between CA and TB is known as temporary difference. The difference is temporary because the difference of $20 only exist from year 1 to year 4. By year 5, there is no more difference between CA and TB (as both are equal to zero).

4. The difference of $20 as shown above is known as taxable temporary difference (TTD) because more tax is payable in the future (i.e. as shown previously, we will be paying extra $5 income tax on top of $25 tax expense in year 5).

5. TTD will result in deferred tax liability (DTL). As more tax is payable in the future, we will need to recognise liability.

6. The DTL of $5 as calculated above represents closing balance of the liability. This is because the TTD is calculated by comparing the closing balance of the CA and the TB for years 1 to 5. As DTL is calculated based on TTD, it follows that DTL must be the closing balance of the liability.

Refer to the following table for the movement of DTL balance:

Year 1

In year 1, we will recognise additional tax expense of $5 and DTL of $5. The double entry is:

Dr Tax expense $5

Cr Deferred tax liability $5

Years 2 to 4

As shown above, there is no difference between the opening balance and closing balance of DTL. As such, no adjustment is required for these years.

Year 5

In year 5, as the closing balance of DTL has become $0, the following double entry is required:

Dr Deferred tax liability $5

Cr SOPL $5

In other words, the tax expense will be reduced by $5 and DTL will no longer be needed.

Conclusion of Methods

Refer to the following table for the tax expense in the profit or loss:

Important Pointers From the Above Calculations

To sum up, let me repeat the important points that we have covered so far:

- Because of the difference in accounting rule and tax rule, there will be difference in accounting profit and taxable profit.

- Such difference will cause the tax expense to be distorted (i.e. effective tax rate will be different, which can misleading).

- To solve this issue, we need to make deferred tax adjustment (the general idea is to make the effective tax rate the same / almost the same for all the years).

- To calculate deferred tax, we need to compare CA and TB. The difference between CA and TB is known as temporary difference. If the difference is TTD, then if we take TTD and multiply it with a tax rate, we will get the closing balance of DTL.

- In general, the difference between the closing balance and opening balance of DTL will be charged to the profit or loss. Note that under certain circumstances, the deferred tax can be charged to the other comprehensive income (this is covered in Part 2).

Points no.4 and 5 above are very important, so make sure you read them properly. Remember, when we multiply temporary difference with tax rate, we will get the CLOSING BALANCE of deferred tax.

Allow me to continue my explanation a little bit further before I conclude Part 1.

When we talk about the difference between accounting profit and taxable profit, the difference can be either:

- Temporary difference; or

- Permanent difference.

Let's look at the two items in more details below:

Temporary Difference

As illustrated above, the difference between the CA and the TB of the asset are temporary differences. Generally, the difference will be temporary if it is due to timing difference (i.e. as shown previously, the temporary difference between CA and TB in year 1 to year 4 is due to the difference between depreciation and capital allowance, which is essentially the difference in the timing of the deduction).

Temporary differences are differences between the carrying amount of an asset or liability in the statement of financial position and its tax base.

Temporary differences may be either:

(a) taxable temporary differences, which are temporary differences that will result in taxable amounts in determining taxable profit (tax loss) of future periods when the carrying amount of the asset or liability is recovered or settled; or

(b) deductible temporary differences, which are temporary differences that will result in amounts that are deductible in determining taxable profit (tax loss) of future periods when the carrying amount of the asset or liability is recovered or settled.

If the temporary difference will result in more taxes to be paid in the future, it is known as taxable temporary difference (TTD). TTD will result in deferred tax liability (DTL).

If the temporary difference will result in lesser taxes to be paid in the future, it is known as deductible temporary difference (DTD). DTD will result in deferred tax asset (DTA).

Consider the following definition from IAS 12 in relation to deferred tax liability and deferred tax asset:

Deferred tax liabilities are the amounts of income taxes payable in future periods in respect of taxable temporary differences.

Deferred tax assets are the amounts of income taxes recoverable in future periods in respect of:

(a) deductible temporary differences;

(b) the carryforward of unused tax losses; and

(c) the carryforward of unused tax credits.

Permanent Difference

To understand permanent difference, let's consider the case when an entity purchases a land for $1 million.

Assuming the land is a freehold land which is not depreciated. As such, the land will have CA of $1 million.

However, for income tax purpose, land is not a qualifying asset (i.e. no capital allowance can be claimed). As such, there is no asset for tax purpose (i.e. tax base of this asset is zero).

The difference between the CA and the TB is therefore $1 million ($1 million CA minus $0 TB).

However, as there will be no deduction given for land for income tax purpose (i.e. no capital allowance is given), the difference between CA and TB is a permanent difference (the difference will be forever $1 million starting from day 1 until the land is disposed off).

|

| Forever alone or forever permanent? |

Accordingly, no deferred tax is recognised for permanent difference (i.e. we can ignore permanent difference in calculating deferred tax).

|

| One of the happy things in FR exam - ignore deferred tax. Yay! 😂😂😂 |

Some other examples of permanent difference includes items that are not deductible for tax purposes (e.g. entertainment expenses to potential customer, penalty and fines). The differences are permanent because such expenses are forever not deductible for income tax purpose. Accordingly, we can ignore them for deferred tax purpose.

Conclusion

After reading through this post, you will have a rough idea on what is deferred tax as well as the rough ides on how it is calculated.

In the next post(s), we will talk about different types of assets and liabilities in the Statement of Financial Statements together with how do we determine the tax bases for these items. We will also talk about how do we determine whether the difference between CA and TB is TTD or DTD.

Stay tuned for more post! 😉

You can like my Facebook page to receive the updates on my blog. Thanks for your support!

Part 2 Link: https://tysonspeaks.blogspot.com/2019/09/ias-12-how-to-determine-tax-base-part-2.html

After reading through this post, you will have a rough idea on what is deferred tax as well as the rough ides on how it is calculated.

In the next post(s), we will talk about different types of assets and liabilities in the Statement of Financial Statements together with how do we determine the tax bases for these items. We will also talk about how do we determine whether the difference between CA and TB is TTD or DTD.

Stay tuned for more post! 😉

You can like my Facebook page to receive the updates on my blog. Thanks for your support!

Part 2 Link: https://tysonspeaks.blogspot.com/2019/09/ias-12-how-to-determine-tax-base-part-2.html